In my capacity as a gender equality activist, I recently attended a conference titled Work/Force: masculinities in the South African media. Hosted by the Department of Visual Arts at Stellenbosch University and the University of Cape Town’s African Cinema Unit and Centre for Film and Media Studies, the conference explored the multiple masculinities put forward by the media in our nation.

Different aspects of masculinities in South Africa

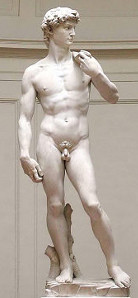

Work/Force speakers discussed perceptions and realities of fatherhood and child maintenance; masculinities in rugby, crime fiction, art, Men’s Health, and Christianity; lawns (?!); the racial dimensions of gay online dating; masculinities in various cultural forms; penises and ‘The Spear’; and more, with a focus on the media. While this gathering focused on masculinities, discussions were heavily informed by feminist theory and gender equality. In other words, it was not a conference of delegates seeking to increase the rights of men at the expense of women. In fact, Work/Force embodied the opposite of patriarchy. People across the spectra of gender, sex and sexual preference talked together, listening to each other for two whole days, about masculinities. While patriarchy was discussed, patriarchy itself would have not been able to survive in such an environment without ruining everyone’s presentations and shutting down discussion with attempts at control, hierarchy and power. And it probably wouldn’t have listened, really listened, quite so respectfully.

At the heart of Work/Force was the idea that Masculinity is really masculinities, that there are infinite ways of performing or claiming masculinity for oneself, despite what much of the media construct to be a homogenous Masculinity, capital ‘M’. When we consider masculinities, we begin to realise that so much of what men do and say is censored or self-censored to fit patriarchal ideas of what a man should be. In fact, patriarchy has far more ideas about what a man should not be that what he should be. But it’s not all doom and gloom for men.

From violence to fatherhood

One global trend in work with men is a shift from negative to positive framing – one example is the widespread move from a central focus on violence to a focus on fatherhood. It is a shift that highlights the potential of men to be caring, loving and, perhaps, better fathers than their own fathers were to them. In addition to curbing myriad psychological problems associated with absent, deceased or uninvolved fathers, encouraging men to be more involved fathers provides a situation where other negative masculine behavioural norms can be challenged. Robert Morrell, editor of Baba: Men and Fatherhood in South Africa, presented some striking research from a Latent Class Analysis. Men who reported more love for their fathers were found to be less likely to have a mistress, to rape, to be in a gang, and more likely to be involved in their own children’s lives, and to be married.

President Zuma’s influence on gender politics: discussion

Of particular interest to me were panellists Amanda Gouws, Commissioner for Gender Equality, and Kopano Ratele, Professor in the Institute for Social and Health Sciences at UNISA, who discussed Zuma’s influence on gender politics at a Work/Force lunch panel. They agreed that the kind of masculinity played out by our President is not one that contributes to building gender equality in South Africa. Though his polygamous life is sanctioned by the Constitutional protection of cultural practices, his comment that single women are “a problem,” is not. His now-retracted comments that he said while speaking “as a man,” (his words and justification for the following) are also unconstitutional: that same-sex marriages are “a disgrace to the nation and to God,” and that, “when I was growing up, an ungqingili (a gay) would not have stood in front of me. I would knock him out.” Zuma uses the trope of patriarchal masculinity to justify these unconstitutional strains of thought and behaviour, perhaps in the hope that other men around the country will identify with him on the sole fact that they have penises, and are men.

Of particular interest to me were panellists Amanda Gouws, Commissioner for Gender Equality, and Kopano Ratele, Professor in the Institute for Social and Health Sciences at UNISA, who discussed Zuma’s influence on gender politics at a Work/Force lunch panel. They agreed that the kind of masculinity played out by our President is not one that contributes to building gender equality in South Africa. Though his polygamous life is sanctioned by the Constitutional protection of cultural practices, his comment that single women are “a problem,” is not. His now-retracted comments that he said while speaking “as a man,” (his words and justification for the following) are also unconstitutional: that same-sex marriages are “a disgrace to the nation and to God,” and that, “when I was growing up, an ungqingili (a gay) would not have stood in front of me. I would knock him out.” Zuma uses the trope of patriarchal masculinity to justify these unconstitutional strains of thought and behaviour, perhaps in the hope that other men around the country will identify with him on the sole fact that they have penises, and are men.

But there is a new consciousness among men. Masculinity that overrides the decisions of others and does not allow men the freedom to choose their beliefs, lifestyles and sexual partners is only one of many masculinities from which men are free to choose. I am pro-choice, and he who justifies misogyny and violence in the name of masculinity walks a dangerous line. The day of plural masculinities has dawned.