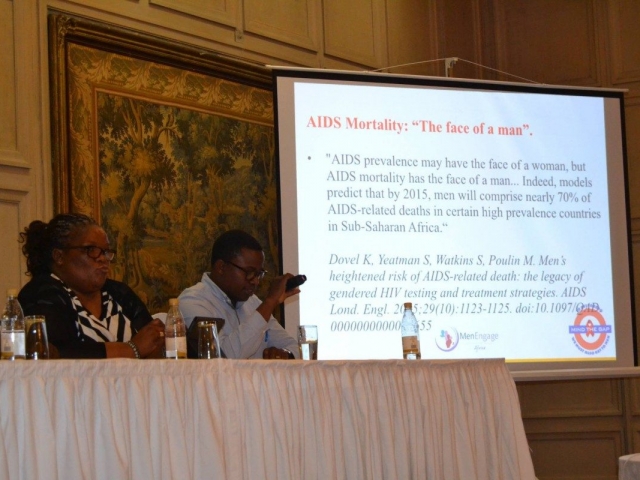

While HIV disproportionately affects women and girls and, as a result, it is said that HIV has the face of a woman, men are more likely to die from HIV-related causes. It is estimated that 70% of all AIDS-related mortality rates occurs amongst men. Thus, men are the face of AIDS mortality.

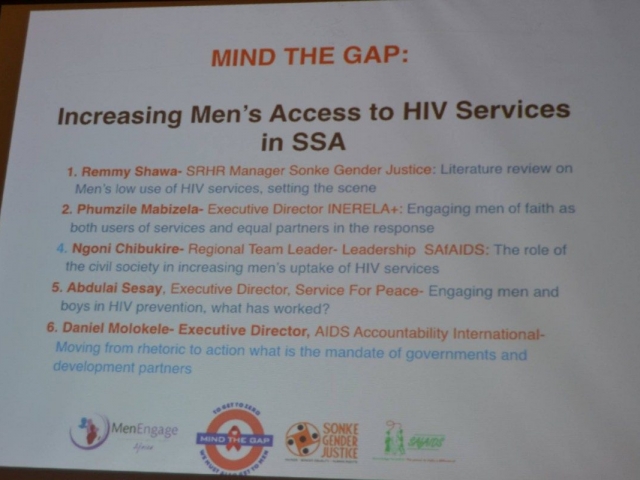

“The AIDS response is leaving men behind”, said Remmy Shawa, manager of the Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights portfolio at Sonke Gender Justice, at a side event at the International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa (ICASA), organised by the MenEngage Africa alliance and Sonke Gender Justice last night to discuss the low uptake of HIV services by men.

“Gender inequality continues to drive the HIV epidemic. Men are under-represented in HIV testing and treatment services. Fewer men are accessing HIV treatment services in Africa. HIV policies have insufficient focus on ensuring more men get tested. Fewer men begin and adhere to treatment and when they become ill, the burden of care fall on women. Not only are men not accessing HIV services, their general health-seeking behaviour is poor”, Shawa told the meeting.

Attesting to this, Reverend Phumzile Mabizela, a religious leader who lives openly with HIV and works with the International Network of Religious Leaders Living with HIV and AIDS, said, “in my own life I had to pray and beg my late husband to test for HIV”.

Various factors contribute to this poor health-seeking behaviour amongst men. “These include cultural norms and negative notions of masculinity, male gender norms associated with toughness and control, sexual prowess and hetero-normativity and low risk perceptions among sexually active men”, said Shawa.

“Over 50% of the population in Africa is the youth. We can’t engage men and boys without engaging youth. Youth are the most vulnerable population when it comes to HIV/AIDS and other diseases”, said Adbullai Abubaka Seysay of MenEngage Africa Sierra Leone.

“In order to increase the demand for services, there needs to be a transformation of gender norms and – at policy level – we need policies that directly speak to men’s health-seeking behaviour and have targets to that effect. Financing of health systems need to be improved and there also needs to be an improvement of health service delivery. All these will improve access to, and utilisation, of HIV services amongst men”, said Shawa.

This also points to the need for role models to encourage men to test for HIV infection. Speaking of INERELA’s work, Reverend Mabizela said “the work that we do is led by reverends, imams, sheikhs… religious leaders from all faiths. We seek to create safe spaces within our congregations where all can talk about their fears and challenges around HIV. We encourage religious leaders to get tested first. That encourages other men to test. We use a lot of theologies that promote life”.

She pointed out that the network seeks to give a human face to HIV as well as to use the influence of religion to educate and create awareness around HIV. “Members of the network have lived with HIV for more than 10 years. One of the things that we have to demystify is that religious leaders are ordained and, therefore, they are immune to HIV. We want to show the world that we are human, too. We decided to use our own stories of living with HIV to encourage people to live positively with their infection”, she said.

Mabizela spoke out against charlatans who use faith healing to dissuade people from taking their antiretroviral medicines. “We have to create a space to talk about the pros and cons of faith healing in Africa. We have found that those prophets – mostly male – have stopped taking their own medicines and are causing people to disrupt their treatment”.

“As a network, we have also decided that the ABC (Abstain, Be faithful and Condomise) strategy moralises the response to HIV. Our alternative to the ABC strategy is SAVE – Safer practices, Access to nutrition and treatment, VCT and Masculinities”, she said.

“When it comes to the issue of sexuality, religious leaders have been at the forefront of promoting stigma by our rejection of sexualities. The problem is we don’t understand our own sexualities and, therefore, we reject other people’s sexualities”, Mabizela said.