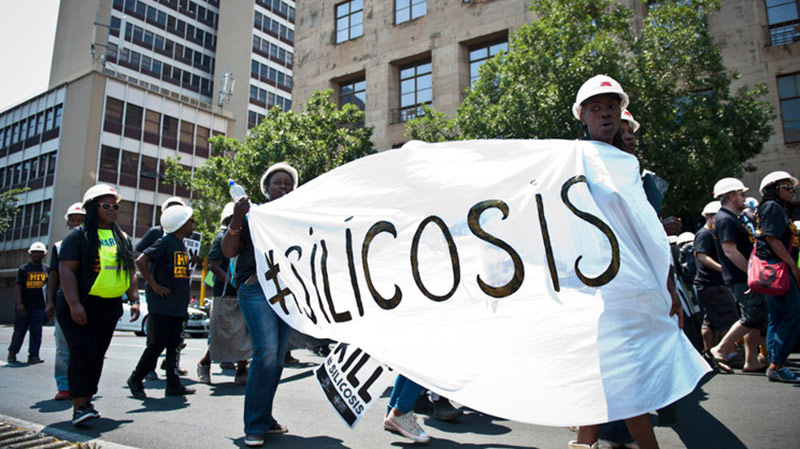

The gold mining industry has applied to appeal the high court decision allowing gold miners to proceed with a class action lawsuit to claim damages for silicosis acquired on the mines. Among other objections, the companies are challenging the court’s decision to meet the needs of the widows and dependents whose lives were also gravely affected by silicosis.

The Johannesburg high court’s May 13 ruling allowing up to 500 000 miners to seek billions of rands in compensation for silicosis was a major victory for mineworkers. It was also a significant victory for women and children.

Silicosis is an incurable lung disease caused by inhaling silica dust. It scars the lungs, restricts breathing and increases vulnerability to tuberculosis (TB). Mining companies can prevent silicosis by controlling dust and giving workers respiratory protection. The compensation being sought includes general damages for their pain and suffering and loss of the amenities of life.

But what about the women and children who have depended upon and supported these workers? They too pay a heavy price.

Sonke Gender Justice and the Treatment Action Campaign were admitted as amici, represented by SECTION27, to give evidence on the gendered impact of silicosis and TB developed from the gold mines.

We made the case that, for decades, the mines knowingly displaced the burden of caring for sick mineworkers on to women in rural areas at physical, emotional and financial costs. The mining companies didn’t contest our evidence.

Courts ruled for compensation for gold miners affected by silicosis, but what about the impact years of caring for the sick had on women and children?

Caregivers

From research Sonke conducted in the mine-sending areas of the Eastern Cape, we learned that caregiving becomes a nearly full-time effort.

As one woman said: “I used to carry [my husband] around. I used to go from house to house asking for food. We had children in school … I would get piece jobs so we could eat.”

Another woman said: “If we had money, [my husband] sent it. During his last days … he could not go outside to relieve himself, so he would do it right there in the bed … On his last day his chest closed up completely. I am left with almost nothing. But I try my best because I am a mother.”

Girls are often pulled out of school so that they can look for work or caregive, for which they are too young and unequipped.

As one woman described: “[We] have no money … some children had to stop going to school. She looked for piece jobs … then fed us and became the parent.”

Girls’ lack of secondary education is also a risk factor for HIV infection, gender-based violence and being in inequitable relationships later in life.

Compensation and court rulings

The mining companies have historically turned away those seeking compensation despite more than a century of profits they’ve gained by exploiting black miners and the families who cared for them.

The high court ruling remedied some of the gendered injustices in this case. It decided that a deceased miner’s claims for general damages can now transfer to his estate regardless of whether he dies during the litigation.

Previously, claims extinguished when the plaintiff died before the suit progressed past the close of pleadings.

The high court emphasised its constitutional imperative to develop common law consistently with the values enshrined in the Bill of Rights, including the rights of women and children.

Although a personal remedy, general damages extend benefits to plaintiffs’ families. Here, they could ease the burden on women and girls caring for miners, and indirectly compensate them for the unpaid care they’ve already provided. It allows resources to provide for children and keep them in school, which aligns with the constitutional guarantee to consider the best interests of the child.

Damage done

The judges found it untenable that outdated common law should benefit the very companies that caused these diseases. With high mortality rates for silicosis and TB – 14 applicants have already died – the mining industry could have played a waiting game and delayed the lawsuit’s progression until more plaintiffs died, thereby eliminating general damages claims.

Removing this limitation on inheriting general damages claims has implications beyond this case. It applies to class actions and individual lawsuits and removes the pressure on sick and dying plaintiffs to rush through litigation. It eliminates the incentive for defendants to delay case progression.

We’re disappointed that the mining companies contested the expansion of transmissibility of general damages to widows and dependants of miners. This continues the industry’s disregard for its sick and dying workers, and the women and girls who cared for them.