This article was originally written for ABC News

By Candace Smith

Gender-based violence knows no borders, but in South Africa, femicide – the killing of women – seems to have touched every woman of every walk of life, and from every social sphere.

Delphine, a South African survivor of domestic abuse who asked that her last name remain anonymous, is one of the lucky ones – she is still alive.

She told ABC News of the abuse she endured at the hands of her ex-boyfriend and the father of her children.

“I remember my first slap that he gave me,” she said. “I was shocked,” she added, pointing to where she was first hit.

It would become a cycle of abuse, she said, one that would nearly break her.

South Africa has one of the highest rates of violence against women on the entire continent, with a rate five times the global average, according to a 2015 study by the South African Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation.

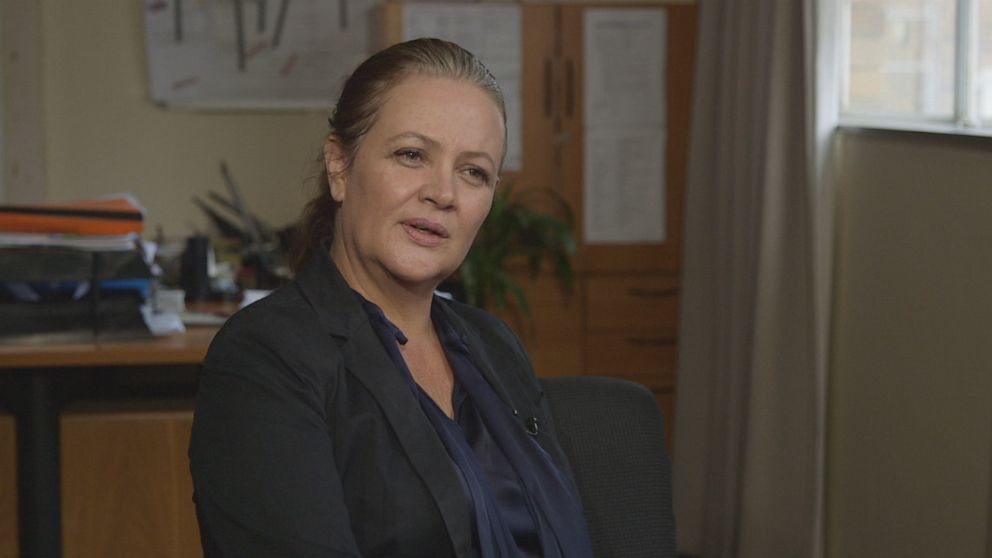

Bernadine Bachar, director of the Saartjie Baartman Center for Children in South Africa, called those statistics “shocking.”

“Statistics suggest that one in five women have been exposed to physical abuse,” she said. “Globally we have one of the highest rates of gender-based violence.

In the U.S., approximately three women are killed every day by a current or former intimate partner. In South Africa, a woman is killed every four hours.

In 2017, Karabo Mokoena became the face of domestic violence in South Africa after an ex-boyfriend killed her, and burned her body.

Susan Shabangu, the minister for women in the presidency, was accused of victim blaming after she said that the victim “came off very strong, but internally she was weak and hence [a] victim of abuse.”

Other cases of femicide have made headlines in South Africa over the past few years.

Valencia Farmer was just 14 years old when she was gang raped and murdered. Her killer was sentenced 17 years after her death.

The Saartjie Baartman Center for Women allows survivors of domestic abuse to live and work with their children.

“Gender-based violence knows no socioeconomic sector. It knows no educational sector. It is part and parcel of every part of our society,” Bachar explained. “We can’t pinpoint one part of the community that is more exposed to it. It is. It crosses all barriers and all boundaries in our society. It’s not just, you know, the richer people or the poor people…It’s across the board.”

Bachar, along with other experts, believes that gender-based violence is prevalent in South Africa because violence has been ingrained in the fabric of South African society.

“Violence has become normalized,” she said. “It’s just part of what we experience on day-to-day basis.”

Gareth Newham, head of the justice and violence prevention program at the Institute for Security Studies, said that historically men feel “entitled” to take a violent approach to things.

“South Africa has always had a violent situation – apartheid was a very violent system,” he said.

“Women and children are susceptible to violence because of the culture of violence where many men believe that they are entitled to use violence against their partners and their children in order to compel compliance with whatever the man wants.”

The effects of violence towards women are on full display at the center where ABC News first met Delphine, who survived domestic abuse and now lives safely with her two daughters.

“I grew up in 1989 in Rwanda, Kigali. I moved from Rwanda at the age of three. I’ve traveled quite a bit – I buried my mom, my dad, my sister in Congo,” she said.

Delphine detailed her past with physical abuse, and said she would “actually prefer being slapped around” because verbal abuse is “very hurtful.”

When she was six months pregnant with one of her children, Delphine’s ex-boyfriend told her, “I’m the reason as to why my parents are dead. I’m bad luck.” She said he did “a very good job” of trying to break her mentally.

The turning point for Delphine came when she was pregnant with her second daughter.

“He’s gone out the whole day and he comes back reeking of alcohol, reeking of cigarettes, and I’m like, ‘So, what are we gonna eat?’ And that’s where the whole fight just started,” she recalled. “He started beating me and I ran to the neighbor.”

Delphine said that her then-five-year-old daughter, Deborah, stood in front of her in an attempt to protect her mother.

That moment, Delphine said, “gave me strength to actually just say, ‘She doesn’t deserve this. She deserves better.'”

“That’s what set me off,” she said.

Delphine moved to the center and lived there for over a year while she worked at a spa. But when her allowed time at the center came to an end and she moved out, she struggled to find work to support herself and her daughters.

She said that for all she has lost, she still found power amid her trauma.

“I’m stronger than before. I’m so [much] stronger than before. I think I’m ready to face the world and achieve the best that I can for them,” the mom of two said.

When it comes to the future of the South Africa, Delphine said her hope is that people say “no” to abuse.

“No to child abuse, to woman abuse. No one deserves to be abused,” she said. “It’s a big no.”

‘Change is a process’

Across the country, in the Eastern Cape, Patrick Godana, looks around at a group of men and women, his hand raised in a fist as he ushers in their meeting with an old chant.

“Long live the spirit of Nelson Mandela,” he shouts.

“Long live!” the crowd echoes back.

But the crowd today isn’t talking about apartheid, the system of racial oppression that Mandela fought against; instead they’re focused on a different sort of justice.

“In the olden days, the apartheid regime said whites are the chosen nation in this country and therefore we lived under apartheid, glorifiied by old Dutch church,” Godana said. “Was that right? Wrong! Isn’t that so? If we are saying racism is wrong, sexism is wrong as well.”

A former youth fighter against apartheid, Godana is a manager at Sonke Gender Justice, an NGO devoted to gender equity in its many forms.

He said there are “many reasons” for higher rates for violence against women in South Africa.

“I don’t want to justify it, makes me feel bad as a man in South Africa because perpetrators of violence against women are men,” he said. “[It’s] very saddening, [a] sad state of affairs in the country.”

“Gender norms are fueling violence against women, social norms are fueling violence against women, alcohol abuse and poverty, because some men feel like they are less of a man, their esteem as men is low and therefore they can only present their own authority by shaking and beating up women,” he said. “My responsibility is to look up and say, ‘What can I do as a man to engage other men in making that change?'”

One of the beliefs of the Sonke program is that men should play a primary role in ending gender-based violence, so Godana hosts workshops all across the country in an attempt to transform how men think about domestic abuse.

On this day, Godana was excited. A prince was in their midst – a man who wielded influence within his village. But Khanyiso Mtoto is reluctant. He believed that biologically and physically, men are stronger than women.

Godana tried to convince him to shift his view, by bringing up examples of women in the military, how women take charge and to instead look at them simply as equal human beings.

By the end of their exchange, Godana asks him a question.

“Do you dispute the fact that men and women are basically equal? Forget about the strength. Look at them as human beings.”

Mtoto concedes; women are, in fact, equal, he says.

Another man, Sithile Nohaya, had a change of heart during the exercise and found himself crossing the floor to the side of the room where some men stood to say they view women as strong as men.

“To change is to live in a better country or in a better world. If I don’t change, I’ll stay the way I [grew] up,” Nohaya said.

The change of heart, Nohaya said, was connected to something more personal. Now one of his life’s greatest regrets, he admitted, was that he once beat his wife.

“I’m trying to fix up that scar, I didn’t make a cut, but inside I know that scar was when my wife looked at me, she want[ed] to see a better man because of our children, I’m trying to be a better man,” he explained.

He still lives with his wife, Thumeka, and their three children.

Thumeka told ABC News that the abuse happened when she broke his phone after she noticed him texting another woman.

“After breaking the phone, he beat me up and I told myself I was going back home,” she said. “It shocked me the way he beat me. To the point that my face curved in from his ring and it gave me a scar,” she said. “I took a decision to go home and promised to never come back, but after calming down, I reminded myself of my marriage vows, that I said ’till death do us apart.'”

Nohaya still feels bad.

“I don’t know if she just really forgave me,” he said.

“When I’m sitting alone I just sometime my tears are falling. I just think if maybe I end up maybe killing her, you know, because if you if you’re angry, you can do anything,” he said. “That’s why I say I want to change.”

Part of Sonke’s strategy is to try and reach men when they are young. Viwe Mpokwane, 20, said South Africa has freedom “but no equality” and hopes to see that change.

“I wanted to learn about gender identity, sexism – human rights. I think because here in South Africa – we have a lot of issues based on gender identity because there’s no equality.”

“There should be no oppressors,” he said. “That time has passed. So I don’t need to come back the way things are in South Africa.”

Godana said he knows change does not happen quickly or peacefully, but it is still possible.

“We need to treat each other with respect,” he said. “I need her, she needs me as well [for an] equitable society.”

He explained that the importance lies in a man’s ability to recognize that women are still human beings.

“If you can treat women as full human beings, we don’t look at them as being lesser than us, this will make a difference in the world,” he said.