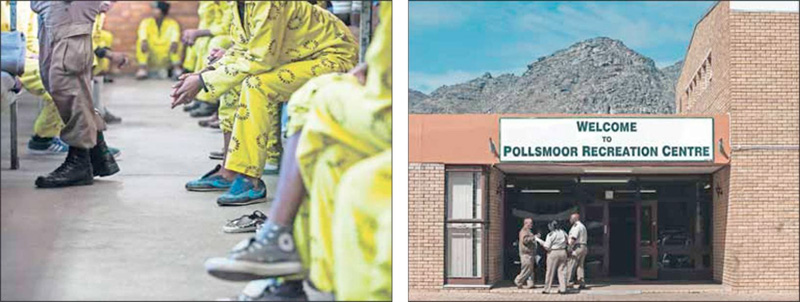

A stay in the Western Cape’s Pollsmoor prison can turn into a death sentence, as was evidenced when two inmates recently died of leptospirosis, a disease spread by rats.

Sonke Gender Justice and Lawyers for Human Rights challenged the life-threatening conditions in the prison last week before the high court in Cape Town. In their application for a supervisory interdict, they claimed the overcrowding in the remand section is a violation of constitutional standards.

If granted, the interdict will compel the government to remedy prison conditions that have been described by Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron as “profoundly disturbing”. The prison head will have a month to submit a report on the remedial action taken.

Eight current and former inmates and those working in the correctional system have deposed supporting affidavits, which paint a dismal picture of the awaiting-trial section of the heavily overcrowded prison.

These inmates, who are legally still presumed innocent, “sleep on the floor. There is one toilet for all of us … There is no privacy for those using the toilet. There is one shower but no hot water. There are about 70 people in the cell at the moment,” writes inmate Peter Maraidjies about the conditions in his communal cell, which was built for 30 inmates.

“On average we are permitted outside the cell for exercise only once a month for about an hour,” says another inmate, Malcolm Brown. “I was granted R500 bail… but I could not afford this amount.”

Emily Keehn, Sonke Gender Justice’s policy manager, said the organisation alerted correctional services, Parliament and the Judicial Inspectorate for Correctional Services to the “appalling conditions” in the awaiting-trial section.

If the high court grants the interdict, the department will be legally obliged to come up with a plan to reduce overcrowding, which fluctuates between 250% and 300%, or about 9 000 surplus inmates, and improve conditions. But first, the organisations want clarity on the prison population.

Clare Ballard, an attorney at Lawyers for Human Rights, says: “We want [correctional services] to tell us how many people are remanded because they cannot afford bail. And how many people are remanded for nonviolent crimes, and who have been awaiting trial for more than two and a half years.”

Instead of incarcerating these groups, noncustodial solutions should be sought, the litigants claim.

Three Constitutional Court judges have visited the facility and criticised the inhumane prison conditions. In 2010 Judge Johan Froneman and in 2012 Judge Johann van der Westhuizen urged action to be taken to address the lack of exercise for inmates, insufficient meals and shortages of medical personnel.

In 2012 Dudley Lee, who spent four years awaiting trial, took the government to the Constitutional Court because he contracted tuberculosis (TB) in Pollsmoor. The court ruled that the department could be held responsible for inmates contracting TB because it had ignored its own regulations. Incoming inmates were not screened for TB, cells were not ventilated and inmates were only let out for short periods of time.

Cameron visited Pollsmoor in April, and in early September published a scathing report on the prison. He documented conditions that the Constitutional Court had deemed unlawful in Lee’s case three years previously: filthy, overcrowded cells with little ventilation, emaciated inmates and insufficient medical supplies. He wrote about inmates with festering wounds and boils who had not seen a doctor. The hospital unit has one doctor and a few nurses to attend to about 4000 inmates.

An official working at the prison, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said four mentally ill inmates told they were being raped after lock-down, when most staff go home. “But the warders say: ‘This is what happens in prison.’”

Mvelisi Sitokisi never saw the hospital unit during his three-month stay in Pollsmoor. He was released in August, when a judge decided there was no evidence against him.

“I told warders I get a light stroke if I don’t take my [antiretroviral medication]. My family brought ARVs to the prison, but the warders said they cannot give it to me. They said they would take me to the clinic.”

But they never did. He had a light stroke. Then his situation got worse. “They gave me just one blanket and I had to sleep on the floor. So I had to decide: Do I cover myself or do I sleep on the blanket with my clothes? In the cell, sick and healthy people are mixed. In the end, I caught TB.”

When Sitokisi left Pollsmoor, he was at death’s door. His clinic put him back on ARVs and TB medication. Although he is happy to be alive, his life has changed irrevocably. “I lost my job as a car mechanic. I am an innocent man, but Pollsmoor prison nearly killed me. It ruined my life,” he said.

Hip-hop artist Bonzaya’s brief stay at Pollsmoor turned into a death sentence. In August last year, he was arrested in Observatory, allegedly with a bag of dagga.

Ra-Mava Ntontela, Bonzaya’s friend and DJ, said: “He was strong, ate healthily, didn’t drink much. He didn’t have money on him for bail, so they brought him to Pollsmoor.”

After eight days, when friends bailed him out, Bonzaya (27) was a different man.

“I was shocked when I saw him. He was coughing and had lost a lot of weight,” says Ntontela.

When he went to his family home in September, his mother took him to a clinic, where he tested positive for TB. His condition deteriorated and he died of kidney failure.

The department admitted after Cameron’s report was published that leptospirosis had claimed the lives of two inmates. The department is now moving inmates to other prisons, or to other sections in Pollsmoor, so the cells can be cleaned and fumigated.

The World Health Organisation says leptospirosis has a “variety of clinical manifestations … from flu-like illness to a serious and sometimes fatal disease” such as Weil’s syndrome, characterised by renal failure, jaundice, haemorrhage and myocarditis; meningitis; and pulmonary haemorrhage with respiratory failure.

Another official at the prison, who works in the remand section and asked not to be identified, told of an inmate who was rushed to hospital in July with imminent heart failure as a result of an untreated scabies infection. The inmate, who was in Pollsmoor because he couldn’t afford his R500 bail, nearly died.

That a stay in Pollsmoor can be a death sentence is all the more evident if the acquittal rate is taken into account. Open Society South Africa, which looked at data in three Western Cape courts, says about half of inmates awaiting trial are either acquitted or released because of a lack of evidence.

The urgency of the life-threatening conditions at Pollsmoor contrasts with the department’s inaction. A Constitutional Court ruling and three judges’ reports have seemingly not spurred it into action.

Keehn says: “This case seeks a ruling on prison conditions, and to define what the constitutional standards on humane detention means. Most importantly, it seeks a court order that requires [the department] to develop a real plan to address the overcrowding, disease, poor guarding and ill treatment, and to report back to the courts on its progress.”

Despite several requests, correctional services declined to comment.