The article below appeared on Bhekisisa, 29 November 2016

By Nivashni Nair and Suthentira Govender

More than half, 56%, of men in Diepsloot in northern Johannesburg say they’ve either raped or beaten a woman in the past 12 months, according to results from the Sonke CHANGE trial, which were released on Monday. These figures are some of highest rates of violence against women ever recorded in South Africa: they are more than double those reported in national studies.

The Sonke CHANGE trial, a partnership between the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) and gender activist organisation Sonke Gender Justice was conducted this year among 2 600 men in the township. The men were between the ages of 18 and 40 years with an average income of R1 500 a month. Only half had been employed in the three months before the study was conducted.

Of those men who had raped or beaten a woman, 60% said they had done so several times over the past year.

“These levels of violence represent a state of emergency for victims and survivors of this violence,” the researchers said in a study summary.

“They experience serious long-term physical and psychological harm. They experience ongoing fear of repeat victimisation, with little reason to believe that perpetrators will be apprehended or held accountable or that potential perpetrators will be deterred from using violence against them.”

South African Police Service reports show that of the 500 sexual assault cases reported in Diepsloot since 2013, there has been just one conviction, according to the researchers.

Abigail Hatcher, one of the lead researchers from Wits, told Bhekisisa: “If you think that 56% of men used violence against women, and because most of them did so more than once, it is likely that at least half of women in Diepsloot are experiencing it annually.

“But because most of the perpetrators have enacted violence towards a woman more than once, it is possible that they enact violence towards more than one woman at the same time. We estimate that we need care services and shelters for about 60% of the female population in Diepsloot. But except for a small organisation, Green Door, there are zero shelters.”

Green Door consists of three donated Wendy houses; the organisation does not receive any funding. It has only one part-time, volunteer counsellor.

According to South Africa’s 2011 census, 138 000 people live in Diepsloot, about 12 000 people per square kilometre. But residents and organisations in the township say this number is a gross underestimation: most estimate the population to be closer to half a million. If that is true, and if half the population consists of women, about 150 000 (60%) could be in need of care and shelter services.

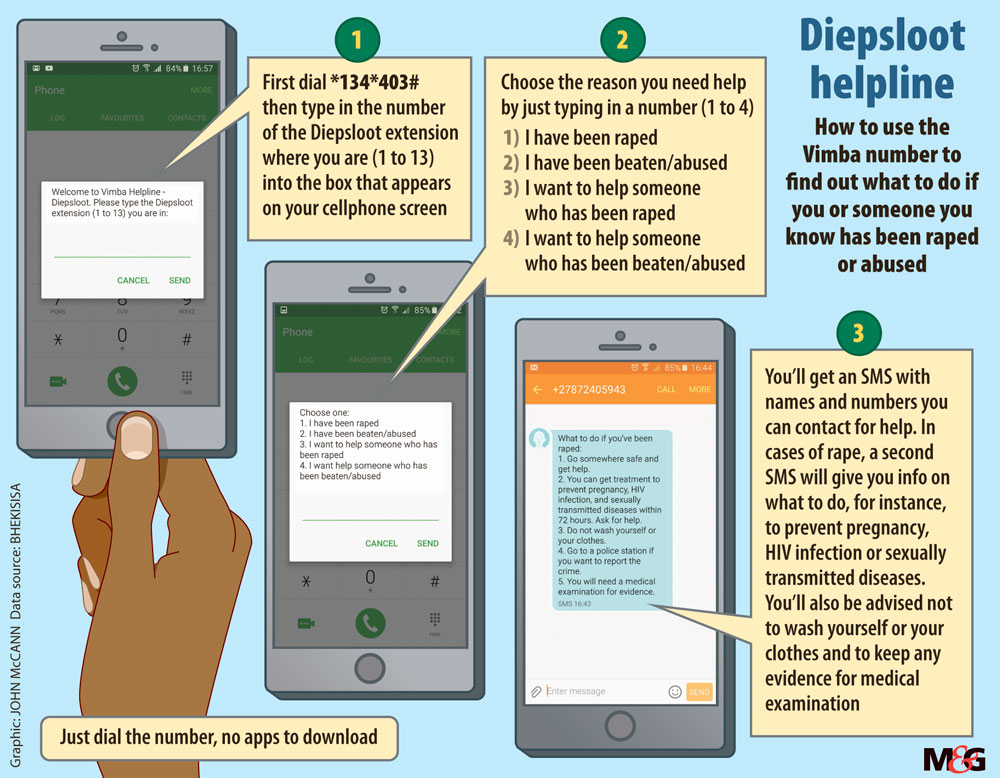

On Wednesday, Bhekisisa will be launching a cellphone app in Diepsloot to make it easier for victims of gender-based violence to know where to find help.

The app is being launched in partnership with Green Door, Sonke Gender Justice, social enterprise organisation Afrika Tikkun, Lawyers Against Abuse and the South African Depression and Anxiety Group.

Users dial *134*403# from their cellphone, which notifies a server to send a series of three menus asking the user where they are in Diepsloot and what sort of help they need. An SMS is then sent to the user with the phone numbers and addresses of the organisations in Diepsloot that help victims of gender-based violence, as well as the numbers of the police and ambulance services.

The Sonke CHANGE trial found that the most significant cause of men’s violence towards women in the township was “inequitable and harmful gender norms that grant men a sense of permission to use violence against women”.

For instance, one out of three men in the survey believe wives should not be able to refuse sex, more than half expect their partner to agree to sex when the man wants it and most believe they have the right to control the clothes a woman wears, the friends she sees or where she goes.

Controlling a partner doubled the odds that men used violence in the past year.

A troubled past, a troubled future

Childhood trauma was closely associated with men becoming abusers: 85% of the men who had raped or beaten a woman had been physically or sexually abused themselves as children. Men who had experienced child abuse were five times more likely to use violence against a woman.

“Children exposed to this violence in the home and community are far more likely to themselves become involved in violence later in life – boys as perpetrators and girls as victims – and are at increased risk of experiencing a host of other social problems, including psychological distress, alcohol abuse, poor school performance and increased involvement in crime, including interpersonal violence,” the researchers said.

Men with signs of depression were three times as likely to be violent towards women; 49.8% of men were found to have probable depression and 50.3% probable post-traumatic stress disorder.

Yet, the Sonke CHANGE trial researchers pointed out that “there are no public mental health services available in Diepsloot to address the mental health consequences of such widespread exposure to generalised violence”.

According to Brown Lekekela, who runs Green Door, the two local clinics don’t stock rape kits and there is no nearby government hospital that offers rape counselling services.

The nearest Thuthuzela Care Centre – a one-stop, government-run service offering rape care – is at Tembisa Hospital about 30km away. “This means rape victims are forced to travel long distances to access post-rape care or to attend court cases,” the researchers said.

The only other available counselling services are those offered by the police and non-governmental organisations. The Gauteng health department had not responded to questions about the lack of services at the time of publication.

Alcohol plays a huge part in exacerbating violence against women. Problem drinking – binge or frequent drinking that interferes with daily life – increased men’s abuse of women by 50%. Three-quarters of the men in the study reported problem drinking. That rate is about six and a half times higher than the national alcohol abuse rate of 11.4%, as reported by the South African Stress and Health survey published in the South African Medical Journal in 2009.

“Men arrive in Diepsloot with a history of violence and abuse in both their childhood and adulthood … the mental health burden on this community is therefore incredibly high,” Hatcher said. “Alcohol is an important self-medication mechanism, a way to ‘take away’ some of these burdens and cares that have really never been addressed by our society. But the problem with alcohol is that it leads to more problems, such as increased episodes of violence.”

The survey showed that men who had a matric qualification, were older than the average participant age of 27 and were employed, were less likely to be violent towards women. Having food security, which is when a household has access to the food needed for a healthy life for all its members, reduced the odds of violence by 40%.

Hatcher said: “When men feel active and productive, and when they’re able to have certainty in their lives about their daily needs, they’re likely to use violence less to prove their manhood.”