Prepare for some bad stats: in July, 18-year-old Sanet de Lange was leaving Tiger Tiger nightclub in Claremont, Cape Town, when she was ‘dragged out of a taxi, kicked and assaulted’, according to her brother, Marius Strydom, who posted a shot of her battered face on Facebook. Three days later, reflexologist Kerri Lehmann, 35, and her partner, Lauren-Lee Poultney, were threatened by metered taxi drivers while putting their bags into an Uber car parked outside the Sandton Gautrain station. ‘They hit the car and pushed and chased us,’ she told COSMO.

A month before these incidents, a 27-year-old Durban saleswoman taking a minibus taxi to visit her flaneé in Hammarsdale was raped. ‘I was the last passenger and the driver pulled over. He said he had to check the lights,’ Mpumi* says. ‘Then he opened the passenger door and pushed me across the seat…’

We put our trust in services that are supposed to offer us a safe form of transport. But, it turns out, as women we’re just as vulnerable in these situations as ever. It makes you think: should you be asking your dad for a lift even though you’re no longer in your teens? Or should you be turning your back on cabs unless you’re sharing a ride with a guy you know and trust? We’ve all heard the stories – are we facing a crisis in cab safety?

CALCULATING RISKS

Police would not disclose figures because of a moratorium on crime statistics but lieutenant colonel André Traut, spokesman for the SAPS in the Western Cape, says that ‘Assaults and related crimes perpetrated in taxis are not regarded as common.’ Kathleen Dey, director of Rape Crisis Cape Town Trust says otherwise. ‘We’ve dealt with many cases, and it’s very common in minibus taxis,’ she says. ‘Women in taxis can be extremely vulnerable at times.’

The typical modus operandi, says Rape Crisis counselling coordinator Shiralee McDonald, is ‘to drive you off to a remote place and rape you’. You are most at risk at night, travelling alone or as the only female passenger. But travelling with other women does not guarantee protection either: in 2013, Eyewitness News reported that two women travelling to Bellville were forced at gunpoint to the floor of a taxi, where three men sexually assaulted one of them. You could also become collateral damage in wars between minibus-taxi associations.

It’s not just minibus taxis that are getting a bad rep. Attacks on Uber drivers and their passengers locally and abroad are prevalent too. They stem from rivalry with metered taxi drivers, who accuse Uber drivers of luring clients with lower fares and not competing on equal ground, as they don’t have taxi-operating licences from the Department of Transport.

In July, Ismail Vadi, the MEC for roads and transport in Gauteng, where incidents of intimidation have been reported at Gautrain stations and airports, announced that Uber partner drivers must apply for metered taxi licences. It remains uncertain whether the rivalry and attacks will end, and Uber users are advised to meet drivers inside stations or in places where there is security.

SEARCHING FOR ANSWERS

Robberies, intimidation and taxi-war killings may grow from the economic disparity and social breakdown that fuels most crime, but reasons behind deliberate sexual assault on women using taxis are rooted in gender issues, says Mbuyiselo Botha, government and media liaison specialist at Sonke Gender Justice. ‘Women are psychologically and physically assaulted daily when they enter taxi spaces,’ he says. ‘Men whistle and touch their bottoms as they get in and out of taxis, and when they sit in front, drivers deliberately touch their thighs when changing gears. Their body integrity is violated, their dignity constantly disrespected. The message is clear: the taxi is a man’s world, where you live by a man’s rules.

‘Because these men are unchallenged by authorities and most women are afraid to report incidents (drivers tell them they know where they live!), they have a sense of impunity,’ he says. ‘It can happen at any time – but if you travel alone at night or intoxicated, you are seen as actively inviting trouble … and they will give it to you.’ Ironically, that is also when you are most likely to turn to a taxi – to ‘get home safely’.

COUNTING COSTS

Attacks on women who use taxis ‘undermine equality and the democratic process’, says Botha. ‘Since 1994, many young women say they will wear what they want and go where they want because it is their constitutional right, but this is challenged daily in taxis.’

On a personal level, the trauma can have huge physical, psychological and behavioural costs, says Dey, including ‘injury, pregnancy, HIV or other STIs, shock, depression, nightmares, thoughts of suicide, isolation from other people, and feelings of anger, extreme anxiety and shame’. These can all impair the survivor’s ability to maintain healthy relationships and function at work.

‘Going out and using taxis is a necessity, not a choice, for many women, and having to use them after being raped in one is a serious hurdle to overcome,’ says Dey. ‘A key symptom of post-traumatic stress is the overwhelming emotional reaction to anything that triggers a memory of the rape, and can include fear, panic, anger or sadness.’

McDonald tells of a client who was raped by a taxi driver while on the way to a job interview. ‘She was no longer able to travel on public transport and for many months wasn’t able to pursue her dream job. She felt that it had altered the course of her life forever. Some survivors lock themselves away from the world, feeling a deep sense of powerlessness and that others have control over their life.’

Mpumi has experienced similar fallout in her life. ‘I’ve been having panic attacks and I still have issues with physical contact,’ she says. In August she had a breakdown at work. ‘My manager sent me for counselling and I spoke about the rape for the first time. It’s helping.’

SEEKING SOLUTIONS

Through counselling, survivors of taxi attacks can master their symptoms and fears, come to terms with what happened and move on, says Dey. ‘But far more needs to be done to make taxis safe for women and prevent this!’

Samantha Allenberg, the Uber communications associate for Africa, says they are ‘streets ahead’ of their rivals when it comes to safety in terms of their system and drivers. ‘Uber riders can see their driver’s photo, name, vehicle and registration, and their star rating (awarded anonymously by riders) when booking,’ she says. ‘They also have access to a live GPS-enabled map throughout their journey and can share this with family, partners or friends.’

Allenberg also says Uber performs rigorous background checks. ‘Partner drivers must have a professional driving permit (PrDP), meaning they’ve undergone police clearance, and also undergo a comprehensive biometric automated fingerprint identification system criminal background check’.

Motjhane Mabote, general secretary of the Gauteng Metered Taxi Council, says metered taxis are also focusing on safety. ‘Our drivers must have a metered taxi operating licence and a driver’s licence with a PrDP,’ he says. ‘We are looking to partner with all municipalities to have some sort of identification that will help our passengers identify a legal taxi. We are also working on developing our own app that will work similarly to Uber, but legally so.’

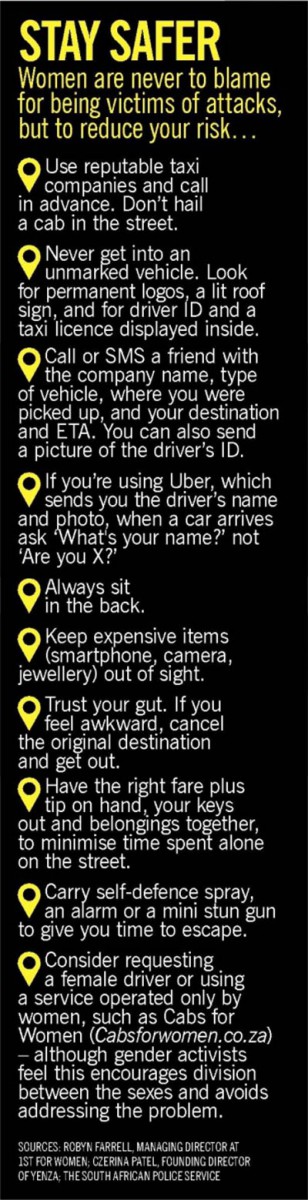

The police say they’re also doing what they can. ‘Frequent operations are conducted by the SAPS in areas with an active nightlife to cater for the needs of patrons of entertainment establishments, and these directions are also directed at the transport industry,’ says Traut. ‘We would like to caution those using public transport to be careful and choose their mode of transport wisely. If you’re going to use a taxi, call on one that is licenced and reputable. Avoid travelling alone, especially late at night; rather move in groups if circumstances permit.’

This attitude places the problem back at the door of women, says Dey, and it’s not a solution. ‘I’m reluctant to tell women to make themselves safer; it’s a form of victim blaming,’ she says.

‘I would rather call on the taxi associations and taxi companies to train and educate their drivers, to vet them better for past criminal records that include sexual crimes before they hire them, and to take all complaints extremely seriously, making it clear a criminal offence has been alleged or committed and will not be tolerated. If oversight bodies take it seriously, it will send a strong message to all their drivers, which can be very effective. Even the Department of Transport should be called on to take the issue seriously; after all, they’re responsible for regulation of all transportation, and their tag line is “Transport is the heartbeat of South Africa’s economic growth and social development!”‘

At the time of going to press, COSMO had not received a response to repeated requests for comment from the Department of Transport.

MEASURING STEPS

Meanwhile, other organisations and governments are attempting to address taxi safety, says Czerina Patel, founding director of Yenza, an empowerment organisation. Last year, UN Women announced a partnership with the City of Cape Town to increase safety of women in public places, especially on public transport – but progress is slow, she says.

‘The minibus taxi system especially is used by millions of South Africans,’ she says. ‘Government needs to put better systems of violence prevention and prosecution in place to improve safety, including increased policing, and outreach and education with both drivers and passengers. As executive director of UN Women, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, said at the launch of the Cape Town Safe City programme, “No city can be considered safe, smart or sustainable unless half of its population – women and girls – can enjoy public spaces without the fear of violence.”‘